George T. Bird might not be a household name like other members of the Cincinnati Bengals family, but if you enjoy the Super Bowl halftime show, or the pomp of college football halftime shows, you should probably give a nod to the man who helped usher in the spectacle known as halftime musical entertainment during the intermission of football contests.

Known as “Red” for his flaming red hair, George began his musical journey in Fayette, Ohio, learning the cornet at age 10 and continuing his musical education through high school. Upon graduation, Bird spent a year with the Dodge Brothers Band in Detroit before enrolling at Ohio State University in 1920 where he joined the marching band. The lure of making decent money as a professional musician was enough for Bird to leave Ohio State and begin work for band leaders such as Jan Garber and Tommy Dorsey.

But life on the road wasn’t as fulfilling as George had hoped and he decided to continue his education at the University of Cincinnati in 1926. He graduated in 1931 with a BS in public school music. He bounced around from Xavier University to Trotwood Madison High and Dayton Steele High before a mentor from his past, changed his life forever.

Massillon superintendent L.J. Smith, a former teacher of Bird in Fayette, Ohio remembered George as being innovative and someone who thought outside the box. Smith had recently brought on the innovative Paul Brown, a graduate of Massillon, to coach the football team and was looking to bring that same energy and difference to the music program.

Marching band routines in the 1930s almost always used what was known as a “pass in review” style of marching. This style was very regimented and military in design and function. Bird brought something a little extra. Although he still used a “pass in review” style, he changed the cadence, the march, and increased the tempo to 180 beats per minute, which proved to be a visually striking difference. Bird also designed a “note cue” concept where band members would use a cue from a musical note in the performance that would indicate a change in direction or a move to another formation.

This concept also gave the drum major a new purpose. Previously known to only lead the band in a rigid march technique, the drum major now was free to become a showman. Bird also incorporated female baton twirlers known as majorettes, and used a tiger mascot to bring even more showmanship to the routine.

As Bird continued to develop this style, he brought props, costumes, and even lighting to his routines. In some instances, Bird would have the stadium lights turned off at cued moments, and used battery powered lights on the hats of the band members and majorettes.

When Bird moved to Massillon, he ended up in a house right next door to the football coach Paul Brown. Their relationship didn’t get off to the best start. Brown later joked that he loathed having Bird as a neighbor because he would be working out band arrangements on his piano at night, keeping him awake.

But Bird and Brown, sharing a common bond of innovation and creativity, became fast friends. And when Brown took over in Cleveland, he hired Bird as director of entertainment. Brown convinced the powers that be of the importance of entertainment. The front office gave Bird a budget of $50,000 to create his dream show.

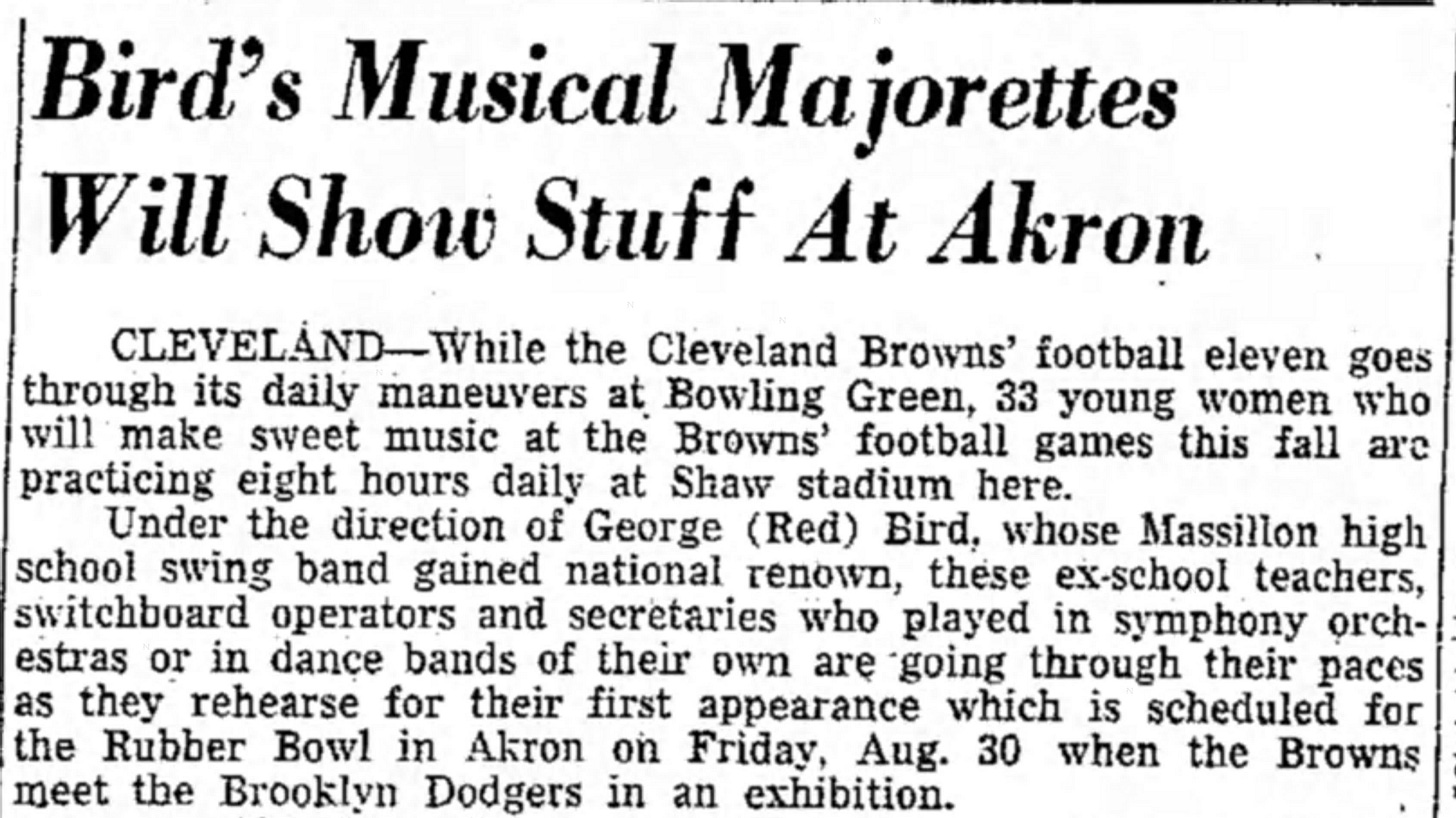

Of course, Bird brought that same innovation and creativity to Cleveland where he formed the “Musical Majorettes” who made their debut at the first Cleveland game, an exhibition at Akron in 1946. Bird was very keen on hiring ladies who could play at least two instruments. Of the four recruited from Massillon, one was his daughter Shirley.

When Brown moved on to Cincinnati in 1968, George Bird came with him. Bird was named the director of entertainment for the upstart Bengals and he brought the concepts that he honed at Massillon and Cleveland with him. He wanted to give schools from Ohio a chance to shine and perform on a large stage and immediately began booking both high school and college bands for the season.

Bird himself conducted a jazz band under a shelter, first at Nippert Stadium, and then at Riverfront. The jazz style 14 piece band was a popular staple during timeouts, between quarters, and dead periods.

When George Bird became ill and was hospitalized that year, he was so frustrated with being unable to do much of anything, he decided to compose a fight song. The “Bengal Growl” was born and is still used today.

Over time, George was unable to continue his duties full-time. He turned the reigns over to his daughter Shirley, who besides taking over the director of entertainment responsibilities, directed Bird’s Band until it stopped performing in 1986.

Below is a clip of Shirley directing the band from 1979.

George T. Bird retired from the Bengals in 1977 and passed away on February 10, 1979.

We must not forget the man who brought showmanship and flair to football halftime shows, and honor his many contributions to the world of music and football.